Don’t (Just) Hate the Tariffs, Hate the Institutions

An overwhelming majority of economists agree: protectionist tariffs harm the very nations that impose them. The notion that taxing Americans for buying foreign goods somehow strengthens our nation is no less absurd now than when Adam Smith dismantled it in the eighteenth century, when Frédéric Bastiat ridiculed it in the nineteenth, or when Milton Friedman disposed of it yet again in the twentieth (subsequently uploaded to YouTube for all of posterity to replay). Yet here we are once again, watching such policies lurch back into public life like economic zombies — this time draped in MAGA hats and nationalist fervor.

Economists have spilled oceans of ink rebutting these ideas. But at some point, we must ask whether the efforts are misdirected. Are we treating the symptoms or the underlying disease? Is the task of the economist to divine “good” policies and “proffer advice to benevolent despots” in the hope that wisdom and power will one day align? Or is our task to examine the institutional conditions under which bad policy becomes possible in the first place?

The economic case against tariffs is neither novel nor subtle. Trade restrictions raise prices for both producers and consumers, stifle competition, and invite retaliatory measures from outside nations. A tariff, in plain terms, is a tax on domestic prosperity masquerading as patriotism.

Yet stylized facts, sophisticated models, endless policy reports, and decades of empirical research have done little to dislodge the protectionist zeal from US politics.

It’s tempting (especially for academic economists) to believe that the solution lies in winning the argument — convincing the electorate, pundits, and policymakers that tariffs are destructive. But that battle has been fought and won, many times over, in journals, books, and classrooms.

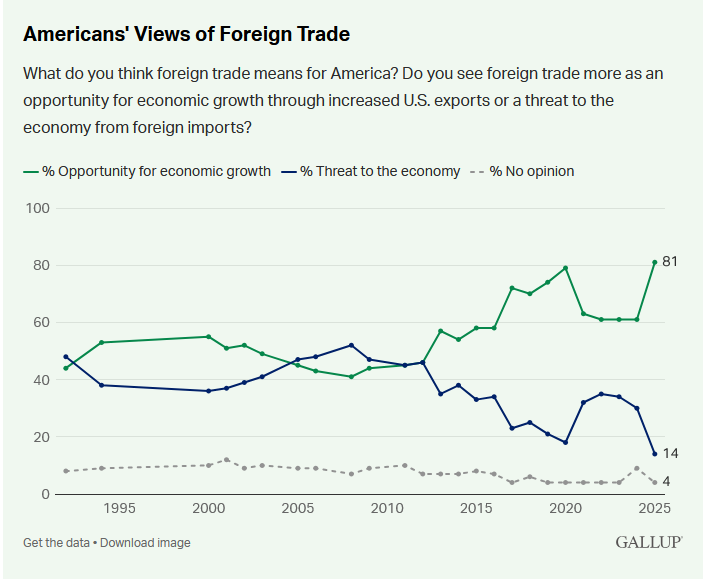

In fact, according to recent polling, 81 percent of Americans see trade as an opportunity for growth — an all-time high since 1992 — while just 14 percent consider it a threat to the economy.

The problem isn’t a deficit of knowledge or sentiment — it’s a surplus of power.

Constitutional Decay

Montesquieu, writing in 1777, argued that liberty depends not on the virtue of those who govern, but on the dispersion of power among them. Madison, in crafting our constitutional architecture, advanced that insight by embedding friction into the process of governance — not to ensure that good policies would prevail, but to make it institutionally difficult for any single actor to impose their preferred policies unilaterally.

But over time, the institutional guardrails that once restrained executive discretion have been steadily dismantled. Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 and Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974, for example, have furnished presidents with broad authority to impose tariffs without congressional approval — often under the vaguest invocations of “national security” or “unfair trade.” Under Section 232, the Secretary of Commerce can initiate investigations — sometimes at the president’s request or even unilaterally — into whether imports threaten national security. If such a threat is deemed to exist, the president has nearly unfettered discretion to act, free from oversight by the ITC or Congress. Section 301, originally intended to enforce US rights under trade agreements, likewise allows the president to retaliate against foreign practices deemed “unjustifiable” or "unreasonable."

The Trump administration did not create these powers; it merely applied them more boldly. His 2019 use of Section 232 to justify tariffs on steel and aluminum rested on tenuous rationale, widely regarded as such even within his own administration. Yet the underlying legal structure permitted it. The authority had been lying dormant, lacking only an actor with the will to use it.

And in case you believe that the legislature might act as a check in the year 2025… think again. Congress has long held the power to revoke the president’s tariff discretion. It simply hasn’t. The discomforting truth is that a sufficient number of lawmakers either support protectionist measures or lack the will to oppose them.

This is not a minor procedural defect — it is a fundamental institutional failure. The concentration of authority in the hands of the executive reflects a broader erosion of constitutional design: the shift from governance by rule of law to governance through discretionary power. As David Hume observed, any political system that depends on the virtue of its rulers is already insecure. “Every man ought to be supposed a knave,” he warned, “and to have no other end, in all his actions, than private interest.” A free nation maintains its liberty not by the character of those who hold office, but by the constraints imposed upon them. Milton Friedman echoed the point centuries later: “I do not believe that the solution to our problem is simply to elect the right people. The important thing is to establish a political climate of opinion which will make it politically profitable for the wrong people to do the right thing.”

Tariffs have not returned because their champions triumphed in the battle of ideas, but because the institutional levees that once held them at bay have gradually eroded.

A Way Forward

F.A. Hayek once observed that Adam Smith’s “chief concern was not so much what man might occasionally achieve when he was at his best but that he should have as little opportunity as possible to do harm when he was at his worst.” If leaders can act on their worst impulses, then safeguards won’t be found in more enlightened rulers but in fewer opportunities for impulsive rule. Liberty, therefore, requires a better game, not just better players.

To view Trump’s tariff program as an aberration, as many economists now do, is to misunderstand the institutional trajectory that made this scenario possible. The same discretionary trade powers he exploited have been employed — albeit with more restraint — by his predecessors. In 2009, President Obama used Section 421 to impose tariffs on Chinese tires, a decision that economists widely criticized as politically motivated and economically counterproductive. President Biden, rather than rolling back Trump’s measures, has preserved and expanded them — particularly in industries tied to strategic competition with China — relying on the same justifications. Even Bernie Sanders, who has long advocated protectionist policies, might well have reached for the same tools had he been given the chance to occupy Trump’s office.

What distinguishes Trump is not the power he holds, but the theatrical defiance with which he exercised it. Much of the outrage directed at Trump is, therefore, misguided. Why not blame any one of his predecessors? Why so little outrage directed at Congress? Why not blame ourselves for the sin of complacency? We knew better… we know better. Or at least we ought to. We ought to know by now that concentrated power is not rendered less dangerous because those who have held it up to now have exercised some degree of restraint. If anything, such discretion may make expansions more insidious by masking potential harms and inviting future demagogues to exploit them more fully. Seen in this light, Trump did not suddenly break the system this week; he stress-tested it, and in doing so, exposed its fragility. The moral panic he provoked says less about him than it does about the complacency of an intellectual culture that had mistaken procedural decorum for genuine constitutional safeguards.

What has shocked the conscience of economists this week should have disturbed it long ago. This machinery did not emerge fully formed from the Trump presidency; it is the predictable result of decades of constitutional drift — tolerated, perhaps, because until recently it was exercised with a lighter touch. But if such power is intolerable in the hands of any one president, then it is indefensible in principle. For too long, economic apology has been advanced in a vacuum, attempting to speak truth to power by virtue of its reason and evidence. Yet truth, absent constraint, rarely travels far in the halls of power. As trade barriers rise by fiat and global markets convulse in response, we are reminded that good policy is inevitably held hostage by institutions. Unless we confront the constitutional permissiveness that enables this economic sabotage, our arguments will remain epiphenomenal — sophisticated, but ultimately irrelevant. The defense of free trade, then, must be paired with a renewed constitutional dialogue: one that might “attend to the rules that constrain our rulers.”

Courtesy of AIER.org and originally published here.

*********