Has the Bear Market been here all Along?

In this week's commentary we will address a topic that has been foremost in our minds for the past several days and has even been suggested by other stock market commentators of late. Looking at the market and its various technical measures we are beginning to wonder more and more if, rather than having experienced a massive bull market topping phase for the past several months, we haven't rather been in a massive and deceptive bear market rally that began in October 1998. The answer to this question will shed much light on where we stand in the grand scheme of things and will let us know what we can expect next from the U.S. market.

As peculiar as our proposal may sound, it is not entirely out of the question that the massive rally from 7400 in the Dow Jones Industrials last October was nothing more than a bear rally. If that was indeed the case then we are technically still in a bear market and can presumably expect conditions to worsen from here. The nature of last autumn's "Greenspan rally" was of the type normally seen in massive short-covering measures by traders on the wrong side of the market. Indeed, much of the fuel for the rally was made possible by the tremendous amount of short interest that existed at the time. This is really the crux of our question, for short covering rallies rarely result in lasting gains and almost never signal the start of a new bull market or the resumption of a previous one. Short covering rallies are purely ephemeral phenomena with results that last anywhere from a few days to a few weeks, to a few months under extraordinary circumstances (ours would obviously fall under the latter case). Short covering rallies can never lead to anything substantial in the way of point gains because traders are not initiating new long positions; rather, they are merely covering their old short positions in the interest of safeguarding against further losses.

Indeed, little has changed since last October in the way of investor positions. According to recent AAII statistics, bullish sentiment is still very high and bearish sentiment is roughly equivalent to where it was last fall. In other words, nothing has changed—investors haven't changed their outlook one way or the other. If the long-term outlook had suddenly changed from bearish to bullish we would expect to see it reflected by the decrease in bears, indicating a change in heart (hence, the initiation of new long positions). Correspondingly, this wide divergence of opinion is the stuff of which major market moves are made of. Difference of opinion is what gives fuel the market and galvanizes traders to take positions based on their convictions of where the market may be headed. Uniformity of opinion can only result in a sideways market since everyone is on the same side of the market. With the current divergence of opinion we can expect a major move—in one direction or the other—in the very near future.

In the broader scheme, the market has been under distribution for at least the past two years. The first piece of evidence for this assertion is the NYSE Advance/Decline line—a measure of market breadth—which has been in a horrible declining phase during the last two years. Expounding on this startling lack of breadth, Alan Newman, editor of Crosscurrents, writes, "Perhaps the best measure of participation is the percent of stocks above their 200-day moving average. In the summer of 1997, this indicator peaked at one of the highest readings we have ever seen, 87%, signifying that nearly every issue on the NYSE was in gear and rising…After a brief correction in the autumn, prices moved far higher but the percentage of stocks above their 200-day moving average continued much lower, eventually trading just above 50% when the market averages peaked in July 1998… In September, only 15% of all NYSE issues were above their 200-day moving average…And even now, after a startling breakout by the major indexes, an 8.2% explosion from the February lows, less than one of every three NYSE issues trades above its long term moving average."

An even more reliable measure of market strength is trading volume. As a rule, volume tends to peak out ahead of prices, usually by a few weeks. Trading volume registered a series of all-time highs late last year and earlier this year only to peak April. Volume has been on the wane ever since, even as prices made new record highs. Commenting on this phenomenon, Robert Prechter of The Elliott Wave Theorist wrote, "The chart of average daily volume for each week over the past two years shows that volume surges have been excellent reversal signals over this span. From April 14 through April 20, [1999], five consecutive trading days were among the 12 busiest in NYSE history! Despite this record high volume, the two weeks ending April 23 saw little upside progress. This price action suggests distribution, which is characteristic of a market top." Prechter also points out that volume surges in October 1997, September and October 1998, and most recently, April 23, occurred when prices were falling—a bearish phenomenon.

Indeed, the Dow's October "Greenspan rally," the biggest one-day rally in NYSE history, registered on the bar chart what is known as a "mid-range closing" on extremely high volume, where prices close in the middle of the day's trading range. A truly bullish reversal signal—a "key reversal"—would have been a close at the day's extreme high point. This would have indicated undeniable buying interest and thus the initiation of new long positions. Instead, we saw evidence of distribution by insiders while the gullible investing public bought into the short-covering rally.

The type of action we are witnessing now frequently occurs at the end of great bull markets. The public is loaded up with stocks and the point of absolute saturation has been reached. The public perhaps would like to buy more stocks but cannot due to their existing commitments and tied up capital. Buying interest is low, in part because of high prices. This accounts for the low volume we have witnessed the past two months as both market declines and market rallies have been on low volume. The point is that without a huge outside injection of liquidity from monied interests further upside potential will remain difficult to impossible. And it would appear the monied insiders have taken leave of the stock market in large numbers.

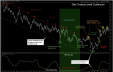

A very interesting phenomenon that would appear to confirm our suspicions concerning a bear market rally is the major divergences seen in the Rydex family mutual funds, which are heavily followed by investment advisors and institutional fund managers. Specifically, we refer to the Rydex Nova Fund, which is positively correlated to the S&P 500 (a bull market fund) and the Rydex Ursa Fund, which is inversely correlated to the S&P (a bear market fund). While the Nova Fund has been climbing from its September 1998 lows to new highs, its MACD indicator has been diverging from the trend almost the entire time. Conversely, the Ursa Fund has been falling for the better part of the past eight months, yet its MACD has been undergoing a positive divergence from the price trend. What all of this means is that the underlying conditions for this "bull market" over the past several months must be viewed as suspect, and the technical picture behind it is of a bearish nature.

A symmetrical triangle pattern is forming in the Dow and resolution appears to be near. Based on the minimum measuring implications of this pattern, a move of approximately 500 points (regardless of direction) can be expected once prices break out from the apex. Also, a small head and shoulders topping formation has appeared in the Dow Jones Utilities which projects a downside move to approximately the 315 level in that index. Based on our turning point work, a penetration above Dow Jones 10900 is needed before the uptrend can be resumed. Below 10900, our Elliott Wave count suggests a major corrective move is underway.