What The Federal Reserve And The Fear Trade Do For Gold

Following the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting yesterday, Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen made it clear (again) that interest rates would not be raised until inflation gains more steam. With current inflation rates negative for the first time since 2009, and with the U.S. dollar index at an 11-year high, we can probably expect near-record-low interest rates for some time longer.

Along with major stock indices, gold prices immediately spiked at Yellen’s news, rising nearly 2 percent, from $1,151 to $1,172. That’s the largest one-day move we’ve seen from the yellow metal in at least two months.

It’s also a prime example of gold’s Fear Trade, which occurs when investors buy gold out of fear of war or concern over changes in government policy.

As I’ve frequently discussed, one of gold’s main drivers is the strength of the U.S. dollar. The two have an historical inverse relationship, as you can see below.

In September 2011, when gold hit its all-time high of $1,921, the dollar index was at a low, low 73. Today, with the dollar having recently broken above 100, the yellow metal sits under a lot of pressure. However, I’m pleased at how well it’s held up compared to the early 1980s, when gold plunged 65 percent from its peak of $850 per ounce as the U.S. currency began to strengthen.

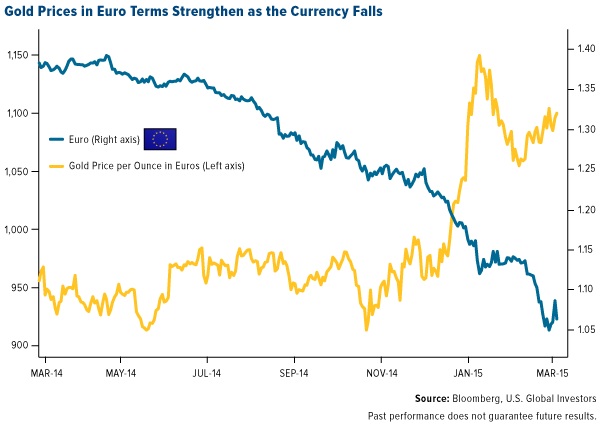

We’re seeing the opposite effect in the eurozone as well as other regions around the world. In the last 11 months, the euro has slipped 24 percent. Many analysts, in fact, expect the euro to fall below the dollar for the first time.

When priced in this weakening currency, gold has climbed to a two-year high.

Real Rates Drive Gold Prices

As I write in last year’s special gold report, “How Government Policies Affect Gold’s Fear Trade”:

As I write in last year’s special gold report, “How Government Policies Affect Gold’s Fear Trade”:

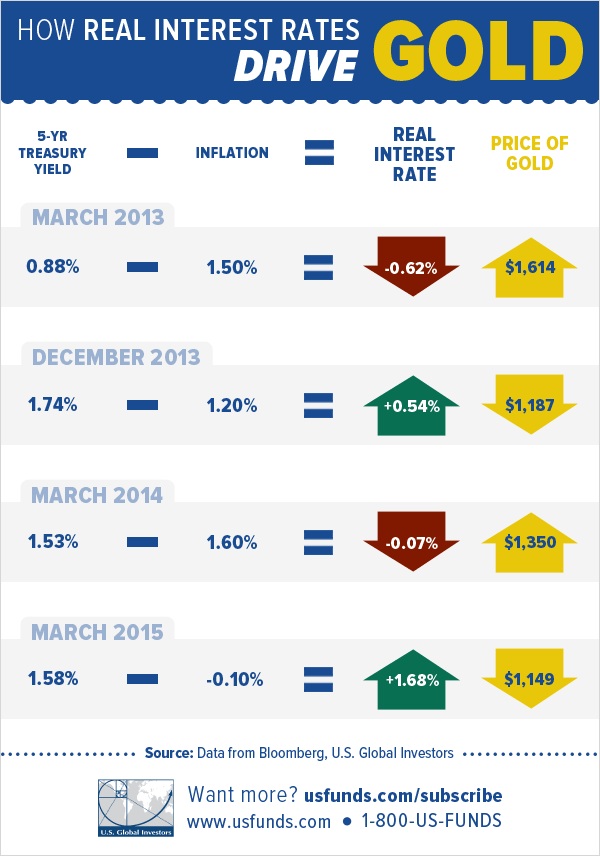

One of the strongest drivers of the Fear Trade in gold is real interest rates. Whenever a country has negative-to-low real rates of return, which means the inflationary rate (CPI) is greater than the current interest rate, gold tends to rise in that country’s currency.

To illustrate this point, take a look at the current five-year Treasury yield and subtract from it the consumer price index (CPI), or the inflationary number. You get either a positive or negative real interest rate.

When that number is negative, gold has tended to be strong. And when it’s positive, gold has in the past been weak.

This month, real interest rates in the U.S. have turned massively positive, putting additional downward pressure on the yellow metal.

When you look at the yield on a five-year Treasury bond in March 2013, you see that it was 0.88 percent. Take away 1.5 percent inflation, and investors were getting a negative real return of 0.6 percent. This made gold a much more attractive and competitive asset to invest in. March 2013, by the way, was the last time we saw gold above $1,600 per ounce.

Because inflation is in negative territory right now, returns on the five-year Treasury are higher than they’ve been in several quarters. Compared to many other government bonds worldwide, the U.S. five-year Treasury is actually one of the very few whose yields are positive, which tarnishes gold’s appeal somewhat as an investment.

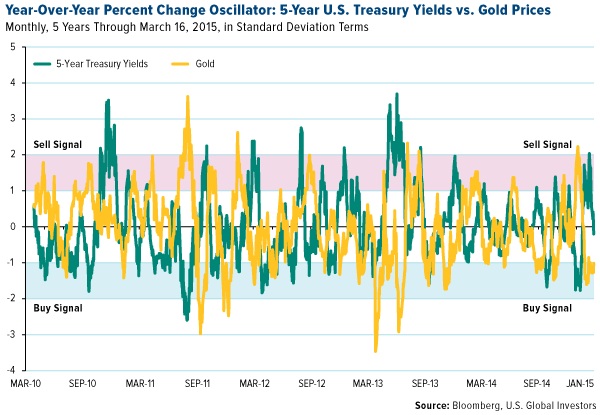

The following oscillator for the five-year period gives you another way to look at the strong inverse relationship between the five-year Treasury bond and gold. As if locked in a synchronized dance, each asset class swings when the other one sways, and vice versa.

This is why it’s so important to manage expectations.

As Ralph Aldis, portfolio manager of our two precious metals funds, said in our most recent Shareholder Report:

You need to use gold for what it’s best at: portfolio diversification… You have to be a bit of contrarian. Buy it when everybody hates it, sell it when everybody loves it. Our suggestion is to have 5 to 10 percent of your portfolio in gold or gold stocks and rebalance once a year. You might also get some additional benefits by rebalancing quarterly. That’s like playing chess with the market as opposed to rolling craps.

Frank Holmes is the CEO and Chief Investment Officer of

Frank Holmes is the CEO and Chief Investment Officer of