Why is Gold Leading the Charge Against the Dollar?

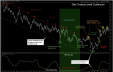

Gold is looking better all the time. A perfunctory look at the accompanying charts prove the, shall we say, omniscience of the call.

The dynamics behind this gold call were spelled out in detail in our October 1, 2001, issue. Below, we present an excerpt of that argument and then add a new and confirming piece of information that has come to light in recent weeks.

After describing the extraordinary magnitude of the global monetary stimulus, we turned to its implications and the possibility of capitalizing on the "inevitable" conclusions. Here, in part, is what we wrote:

"Neither foreign currencies nor industrial commodities are likely to be the early winners the early winner in our view will be gold.

"The special circumstances that brought it so low are disappearing. For one thing, the bulk of demonetization has occurred; henceforth, official supplies are predictable and digestible. For another, forward selling has telescoped future mine supplies, but accelerated supply totals have remained fairly steady. If anything, mines are likely to lift hedges going forward, to take advantage of paper 'profits' and repair weak balance sheets.

"Goldfields reported that mines added to demand by lifting hedges on 41 tonnes during this year's first half. Moreover, it is quite possible that all the gold that could profitably be locked at forward prices was already sold. Further hedging would necessitate much higher prices. But much higher prices are also likely to cause a rush of short-covering, particularly for those mines that need to raise external funds and thus need friendly investors (hedged companies are no fun).

"This spells, potentially, a gigantic short squeeze as short positions are equal to one-year mine supplies. Favorable price action should also awaken investor interest: Last year's divestment and source of supply would turn into this year's demand. The sudden change in the gold equation has the potential of causing a veritable price explosion."

Well, Goldfields' figures for the full year 2001 are in, and the early trend is confirmed: The global producer hedgebook dropped by a not immaterial 147 tonnes. A net reduction in outstanding positions, naturally, implies that gold is being withdrawn from the market. In other words, it should correctly be viewed as an increase in demand. What is significant is that this is the first full-year reduction in many years (there was an minor reduction in 2000 of just 15 tonnes), and it points to an acceleration of the trend--41 tonnes in the first half of 2001, 106 tonnes in the second half. Clearly, hedging is out.

If our assumption that hedging is no longer fashionable or profitable or both (mostly because of bullish prospects for the metal) is valid, which we think it is, the implications are extremely bullish. Here's why. The world supply and demand for gold is finely balanced, with total supply (including official sales of over 500 tonnes per year) at 3,868 tonnes, and total demand (including bar hoarding, but no allowance for investment demand) at 3,722 tonnes. Hedge lifting makes up the difference (last year, as we said, 147 tonnes). The hedgebook totals 3,067 tonnes. A slight acceleration in the pace of hedge lifting, say a 10% reduction of the book, would, ex ante, overwhelm supplies by 150 tonnes (that is, over and above last year's 150 tonnes reduction). This would be accommodated by rising prices, which admittedly would decrease fabrication demand but which would increase, by presumably a far greater factor, investment demand.

One hundred fifty tonnes represents the equivalent of 45,000 COMEX contracts. To assess the market impact of this buying, one needs to compare the 45,000 contracts with some measure of market liquidity. Because volume includes heavy day-trading activity on the part of "locals" and substantial spread trading, both of which have little or no net price impact, we discard average daily volume. Instead, we submit that the more significant figure is the average daily change in the open commitment over some recent period. Changes in the open commitment reflect genuine "ownership" changes. In fact, ownership trends tend to parallel price movements (whether new buying or short-covering) and can thus be thought of as price-making transactions.

Since December 1, prices have advanced $48/ounce on an open interest increase of approximately 90,000 contracts. The absolute average of daily changes of open interest works out to 2,374 contracts. Hence, the 45,000 contracts of potential short-covering represents nothing less than 19 days of trading, a mighty prop to prices indeed!

Consider, however, a more catastrophic scenario (a la Ashanti, September 1999): Gold producers are forced out of their hedges by their bankers because cash flows are mis-matched, i.e., marked-to-market losses are immediate, and revenues are years away. In such a case, hedge lifting can easily represent multiples of 45,000 contracts. For example, a 50% reduction (1,500 tonnes) in the hedgebook represents the staggering sum of 450,000 Comex contracts, or 190 days of trading, probably enough to drive up prices by hundreds of dollars if executed in some rush.

Not only could a Middle East and/or Indo-Pakistani conflict trigger such a catastrophic scenario but, we suggest, so could the simple continuation of the present advance moving through, for example, the 1997 (a year of record hedge selling) highs of $368/ounce.

Watching the tape, we have taken note of the recent "tightness" of daily ranges, bounded by substantial buying on all dips coupled with careful bidding on upticks, a clear attempt not to frighten sellers. This "controlled" action is typical of hedgers and commercials (who may be trying to wiggle out of short positions), not of speculators. In fact, our sense tells us that this market is being driven by hedge lifting, with speculators (futures traders, Japanese savers) playing a much more reduced role.

If our intuition and our math are correct, gold prices are poised to explode on the upside.