It's Tempting This Time to Bet Against the Fed

Investors should never bet against the Fed, of course, but this time it's mighty tempting.

Until last week, the Fed's great and remarkable contribution to America's prosperity lay in the ability of its chairman, Alan Greenspan, to charm Wall Street with a seemingly benign inscrutability that unfailingly passed for wisdom.

He often talked in riddles, allowing investors to draw their own conclusions. Understandably, they came to believe fervently that Mr. Greenspan had everything perfectly under control and that he would never let them down.

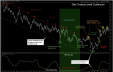

But on Wednesday, with Nasdaq stocks threatening to repeat their pre-holiday cliff-dive, the central bankers laid bare their worst fears, unexpectedly cutting the discount and federal funds rates by a whopping 50 basis points.

Wall Street responded with one of the most explosive rallies in history, and bulls duly praised their merciful savior, Mr. Greenspan.

But other, more objective observers could only wonder how long the celebration would last, and whether Mr. Greenspan, after laying all his cards face-up on the table, would ever again be able to beguile both bulls and bears into submissiveness.

For, while we once believed that a finely shaded reading of statistical ephemera was what drove Fed monetary policy, we now know for certain that Mr. Greenspan and his banking cohorts are as obsessed as the rest of us with the performance of the stock market.

And while we revered him until very recently as a true Master of the Universe, exuding calm detachment and Delphic Authority wherever he went, the Fed chairman now looks more like a nervous wonk with his thumb on the panic button.

To give Mr. Greenspan and his Plunge Protection Team their due, the timing of last week's rate cut -- the first in two years --could not have been more adroit. The announcement came in the middle of the day, just as stocks were beginning to accelerate to the downside after an encouraging early-morning rally.

As the Fed may well have recognized, the market's reversal was potentially serious, for it threatened to intensify the decline in Nasdaq stocks that began, as declines rarely do, in the weeks preceding Christmas and New Year's Eve, respectively.

Even more astutely, it would appear, the Fed stepped in just as several market bellwethers, including the Standard & Poor 500 cash index, were threatening to break below crucial price supports that had been created by bear-cycle bottoms made two weeks earlier, on December 21.

We'll probably never know whether the Fed was watching technical indicators when it acted, but I can report that five stocks in which I held bullish positions that day came within a hair of levels where I had determined to throw in the towel.

Instead, I got bailed out of my mistakes. And although I was pleased to see my losses turn into handsome gains in mere minutes, I was skeptical at day's end that my good fortune would continue for more than another day or two.

Indeed, this rally cannot afford to stall over the next few days if it is to avoid a potentially fatal relapse.

The rally might have been less vulnerable if it had sprung mysteriously from the blue. But as we all know, it was artificially induced by a magic bullet, and that is reason enough for at least some investors to see profit-taking as the most appealing course in the days ahead.

There are other reasons why doubts could quickly mount, turning into a lead ballast. Chief among them is the impending difficulty of reconciling the bullish effects of the Fed's scattershot stimulus with fourth quarter earnings announcements that are almost certain to disappoint, if not sicken.

Because of this, the market is less likely to trend steadily higher over the next month or so than to lurch violently up and down as the mood changes from one day to the next.

While that could conceivably leave stocks higher than they are now, it would take a strong profit rebound over the next several quarters to give investors the gumption to push the indexes to new heights. Absent this prospect, however, shares would probably fall rather than hover.

With the economy already slipping into recession, a do-nothing market would be sufficient to further chill consumer spending, which in one recent quarter accounted for more than 80 percent of GDP growth. By mid-2001, if not sooner, the soft-landing scenario would become a pipe-dream.

Although massive easing by the Fed turned the tide late in the 1990-91 recession, and again in 1998 when the failure of a large hedge fund threatened the entire financial system, in neither instance was the economy glutted with private and corporate debt as it is now, nor was the dollar falling.

I wrote here last year that when the dollar finally turned lower, it would trigger the unwinding of the 1990s global bull market in financial assets.

The deleveraging process may have started ten weeks ago, when the dollar peaked versus the euro at around 83 cents; since then the euro has risen to a recent high as 96 cents. If the central banks were truly able to control currency values, the euro would never have fallen as far or as fast as it did, from a year-earlier high of about $1.18.

In fact, the dollar's strength was driven, not by global trade in good and services, but by its limitless availability to entrepreneurs and financiers around the world, as well as by expectations that it would remain strong relative to all other major currencies.

Now, with U.S. stocks and the dollar falling in tandem, foreign investors are seeing their bets sour. If they should take flight into euros, or perhaps even into gold if panic develops, Mr. Greenspan will have no room to lower interest rates, since that would only steepen the dollar's decline.

By that point, his biggest worry will be deflation rather than inflation. Asset prices will be dropping, corporate profits vanishing, and billion dollar bankruptcies wiping much of today's ethereal "wealth" from the books.

Then, as in 1929, some pillar of the banking establishment will announce that the economy is fundamentally sound and that long-term investors who sit tight will eventually be vindicated.

It would appear that former Federal Reserve Board Gov. Lawrence Lindsey, appointed on Wednesday as President-elect Bush's chief economic advisor, has already gotten the jump on his colleagues in the race for this dubious distinction.

Informed of the Fed's rate cut moments after it was announced, he told reporters, "Great! The Fed is always right."